Christoph Loch

Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge

Stylianos Kavadias Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge

B. C. Yang

Sinyi Realtors and Fu Jen Catholic University Taipei

How do companies translate their strategy into operational actions that support it? Strategists use a different language than operational workers, and often the statements of the CEO have little connection with what the employees do. Christoph Loch, Stylianos Kavadias, and B. C. Yang suggest a tool that can help companies to align their employees’ actions with strategies, clearly explain that alignment, and encourage innovation from the bottom up and collaboration between departments, all in a way that can be completely customized to the company’s strategy.

1. The Difficulty of Cascading Strategy

Translating strategy into action is hard. Many organizations have found themselves in circumstances in which the CEO has developed a sophisticated strategy but, because no one has taken the time to convert big strategy statements into specific targets and plans, the employees end up doing things that do not support that strategy. Likewise, some companies realize too late that they have a strategy and operational plans, but that the two are not aligned. Let us take the example of CCC, a mid-sized European consumer credit company. Exhibit 1 shows its structure at the time of our involvement, which consisted of two business units: an established business partnership with a large retail chain under the partner’s brand and a newer unit designed to help CCC grow a credit business under its own brand. Each unit and the respective support func-tions had been asked by the CEO to develop their individual strategies in the context of the overall strategy.

Both units had ambitious growth plans, though with slightly different emphases. The new business would be based on branding a broad assortment of credit services and providing excellent customer service. The established supplier would enhance the value of its partner through technology, compliance, and collaboration. The strategic plans of the support functions, in the spirit of best practices, emphasized functional excellence, so that the heads and directors could feel certain about their unit’s performance, but none explicitly described or supported the business objectives. Unsurprisingly, given this approach to strategy execution, the company was unable to make decisive progress toward its business goals. Many companies find themselves similarly dead-locked when their various functions are not aligned.

Exhibit 1: The business and functional strategies of CCC

There are four fundamental reasons why companies frequently fail to effectively execute intelligent strategies:

- Weak top-down alignment: Goals are poorly, if at all, articulated or they are inconsistent and fail to contribute to the whole. A typical indication of this problem is the use of generic targets drawn from industry benchmarking, which generally do not support the orga-nization’s specific priorities. The overarching message must be translated into useful and mutual-ly consistent functional, regional, and project objectives.

- Weak bottom-up innovation or modification: Strategy is of-ten treated as an optimization effort, with its planning being rigidly divided from execution. The reality is more fluid: implementing strategy requires creative insights, tracking mercurial market demands, technology opportunities, and competition. The necessary adaptability cannot be achieved solely by analysts at the top. It requires all the information available to an organization, including from frontline personnel, suppliers, and partners. Companies must have a way of incorporating new observations and ideas into their strategy and its articulation.

- Limited collaboration: Too of-ten each unit in an organization adopts its own targets and then pursues them in isolation, as though overall strategic priorities could be achieved by simply put-ting the separate work of disparate units in a heap. But organizations are messy and complex, particularly in the tasks where units inter-act to deliver outcomes. A classic example from the 1980s describes a parts logistics manager who cuts inventories to save costs, thus hurting the service manager who wants to increase customer satisfaction by having parts avail-able to customers at short notice. Unit managers must negotiate their targets and their interrelationships with one another. They must collaborate in responding to uncertainty and share their ideas for better approaches.

- The limited strength of quantitative planning: The uncertainty and complexity of organizations often renders purely quantitative targets insufficient – the numbers are too coarse, difficult to obtain, and inflexible to com-promise. They require complementary qualitative agreements that colleagues can discuss at regular strategic reviews.

2. Tools and Processes

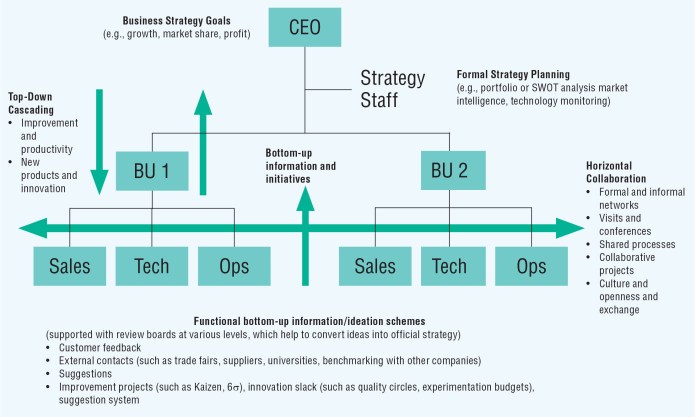

The cascading tree represents a multidirectional (top-down, bottom-up, and horizontal) communication process.

Many companies try to ensure better strategy execution by using score-card tools, such as the balanced scorecard (BSC) and the Hoshin Kanri planning processes. In strategy cascading, however, the great-est challenge is that everything, from decisions about coordination and priorities to management and multi-level discussions, is specific to the particular organization. Nonetheless, in successful companies, managers make sure these discussions reflect a systematic dialogue: from the top down, from the bottom up, and horizontally between col-leagues, teams, and business units. We have observed several such dia-logues which suggest a way, rooted in total quality management, to de-vise an effective process of cascading strategy discussions.1 Exhibit 1 describes the principles by which high-level goals may be translated into operational goals that can be tracked through a simplified (educational) example. Let us suppose that we have set a strategic goal, perhaps shedding those extra kilos. How do we ensure that this lofty mission is successfully put into operation? Let’s trace the steps on the graphic below.

The first step in our cascading effort is to realize that, unless we we will never achieve change because, without clear evidence that we are making progress, we will tend to allow the mission to be overshadowed by other urgent things. So, it is essential to set a target. Let us suppose that our target is to get below 80 kg (for some of us, this may be a very ambitious target).

The second step is to . At the highest organizational level, these actions will be more general and comprehensive than at the operational levels: eat less (calories in) and exercise more (calories out). Makes sense. But these goals are too far removed from the stresses of our day-to-day life, in which we need to monitor whether or not we have acted in pursuit of the mission every day. It is therefore necessary to translate these actions further downward.

The third step is to. So we set a specific target for each action – eat fewer than 2,000 kcal and burn more than 2,500 kcal per day (again, this is brutally am-bitious!) – and develop actions (no chocolate and more veggies, and jog-ging) that are closer to making the plan operational, but still do not de-termine specific actions that can be credibly monitored every day. To get there, we move to a third iteration which dictates actions such as “put veggies on my plate at every meal” (appealing to our impulse to politely empty our plate), and “put the run-ning gear in the way so I stumble over it” which leaves us no excuse to back out. By selecting actions that we can monitor every day, we make our everyday activities support our strategy.

Exhibit 2: A cascade process: the weight-loss cascading tree

The green arrows represent three important features that an effective cascading process should exhibit. Given that top management is responsible for achieving the strategic mission, it certainly needs a top-down element. But who knows what the best actions are? In the graphic, perhaps swimming or aerobics is better suited to our capabilities than jogging, and the people with operational roles know it. Bot-tom-up input is therefore crucial in choosing the activities best suited to ensuring that we execute the strategy successfully. Novel ideas from the operational levels may even suggest ways to improve the strategy. Every-one should therefore have a clear explanation of the strategy and be given the means to articulate their own ideas (and pursue the best ones). Top-down and bottom-up communication is crucial. Finally, none of the actions are independent. No one operates in an isolated silo, so it is naïve to put too much faith in the notion that if everyone just does what they are sup-posed to, we will all be fine. The tough no-chocolate-plus-veggies diet, for example, may make it harder to maintain the motivation to jog. Perhaps one square of low-calorie dark chocolate after each run could act as an incentive to keep jogging. The goals of different departments interact and mutual communication and negotiation are required in order to desi

gn goals that will add up to more than their sum (rather than less when they get in each other’s way). The cascading tree really represents a multidirectional (top-down, bottom-up, and horizontal) communication process :

- Top management articulates (high-level) goals.

- The next level articulates first-level actions (“this is how we can do this”) and negotiates interdependencies between departments: “I need you to support me by doing ‘x’ so that I can achieve my bit” or “don’t do ‘y’ because it will hinder me.” Keeping track of these high level (and often important) inter-dependencies regulates the give and take between departments, keeping everyone honest and making it harder for anyone to get a free ride.

- Departments check their actions by submitting reports to the next level down. Are there better ideas? Are there additional interactions?

- Next, the contributing parties should negotiate how to meet their goals: Can we achieve the goals (or perhaps with a different mix even exceed them)? Top management can choose to take a hard line, or it can be open to change, perhaps in response to the organization’s ambition and innovation.

- The people in those groups that are directly affected by a high-er-level goal (for example, the “less chocolate” and “more veggie” groups in Exhibit 2) should, at this level, discuss the goals together. This conversation will allow them to understand what every-one does, to discuss conflicts, and to discover how, through give and take, they can be more productive together while also holding one another accountable. They are also likely to uncover and negotiate a number of small interdependencies. Although it might be possible to ignore some of these, talking them over renders the re-sulting plan of action more robust, and makes the participants better colleagues, since they have al-ready grappled with conflicts and found recipes for working through them.2

- Make this level’s actions the mis-sions for the next level down, and then start again from step 2. The cascading tree is construct-ed recursively downward, with feedback rising back up. After 3 or 4 iterations, though, further levels become unwieldy and consistency harder to maintain.

Through this process, a portfolio of operational activities emerges, with specific priorities and known inter-dependencies. Sometimes the over-all goals may shift levels, or even dimensions. Moreover a hierarchical goal tree is morphing into a vertical and horizontal series of discussions in which everybody works together to develop organizational performance, everyone is fully informed and understands the operational imperatives, and new ideas emerge and are put to good use. If everyone in the organization trusts that those who offer more will build credit rather than being exploited or reprimanded, the end goal often becomes more ambitious than what was originally proposed.

This cascading process is consistent with four principles which we have identified through our research. These principles are vital to allowing a company to effectively cascade a multi-dimensional strategy.

- Strategy cascading requires formal quantitative targets, just as proposed in the BSC. Without them, it is difficult to act. However, the targets must not be generic, using benchmarks based on other organizations. They must instead be custom-built from the strategy and priorities of their own organization. The straight-forward principle of measuring what you want to achieve, not what others do, is still often ignored, whether for convenience or from a lack of confidence in our own goals.

- Strategy cascading also requires qualitative process targets (commitments to do things). Most strategies are multi-dimensional and cannot be fully captured by one set of targets, particularly when some of the targets are hard to quantify in simple KPIs (key performance indicators). One example is Sinyi’s ethical principles, which we will discuss at greater length below. A cascading tree may contain both quantitative and qualitative tar-gets, including training and socialization, as well as high-level cultural encouragement of less rigidly structured achievements that support the company’s principles.

- Ideas which travel upward from the lower levels are fundamental to this multi-dimensional strategy. Even simple strategies involving, for example, cost performance need bottom-up input to take full advantage of the organization’s wealth of knowledge. This knowledge may spring from sales and marketing in regard to customers, from operations and supply chain management in regard to delivery performance, from accounting in regard to economies, and so forth. This principle is even more important to multidimensional strategies, in which only frontline and middle management understand the subtle interplay of myriad employees’ individual behavior. Successfully cascading a multi-dimensional strategy goes hand-in-hand with adapting that strategy to innovations, most of which rise from below.3 Incorporating these ideas also respects fair process – giving everyone a voice – which motivates people emotionally to contribute rather than resist.

- All three of these principles are underpinned by two organizational capabilities: effective communication and top management behavior. A strategy is not just a conceptual position statement; it is a battle plan that, if all employees under-stand and internalize it, produces alignment. It is therefore vital to ex-plain the strategy to employees, not once, but continuously over time. It is also essential to open information channels through which they can express ideas and offer feed-back. And while strategy cascading is a process (a defined sequence of actions), it cannot be programmed. The whole structure depends on the behavior of the people at the top. If they do no more than pay lip service without actually listening to ideas and feedback, the strength of any cascading process will wither. On the other hand, if senior managers participate sincerely, the transparency which cascading creates will help to control their bias in favor of their own ideas.4

This process does not usually proceed as a set of theoretical questions such as: What are we trying to achieve?, What do we need to do?, or Who will be assigned the tasks? In-stead it is rooted in what is actually there. The discussion moves from strategic imperatives to contributions from the existing organizational units, often passing through several iterations if the initial proposals don’t achieve their aims. This process has two pragmatic implications: first, the resulting cascade is not the only answer; driven by their different processes, capabilities, and cultures, different organizations may come up with very different ways to achieve similar things. Strategy articulation and execution are creative exercises, not the mindless application of an algorithm (indeed, there is no algorithm). Second, the question is not whether the assignment of [theoretical] tasks is complete, but whether every unit has stepped up. In some cases, a particular unit may simply not have any-thing to contribute to a particular goal, but anyone who does not participate sufficiently should bear the consequences.

Let us consider a simple example of cascading strategy from this perspective. This example is based on a project that we undertook with the police department of a city. The department had set the goal of significantly reducing violent crime, especially robberies of residential houses in all vulnerable precincts. The police want-ed to know how to start working to-ward this goal without simply writing checks to add more officers. Exhibit 3 summarizes the cascading process that we developed together.

In a workshop with three hierarchical levels, the police officers first described their target – not eliminating crime entirely, but reducing it by 20 percent (which seemed possible with a feasible resource commitment). They then identified two dimensions of action as being the most promising: increasing patrols by street officers, and educating residents about how they could help minimize the occurrence of robberies. These actions were then assigned specific targets (one patrol per day, one home visit per month). The home visit target could be put into action by one branch of the police (community counselors), while the patrol target would be addressed by frontline officers. After the necessary training and preparation, both groups began to act.

Exhibit 3: Cascading process in a municipal police department

In translating the patrol target into everyday actions, officers from different departments discovered that they could share patrols; al-though traffic cops and municipal street cops were already patrolling, they were working separately, uncoordinated. By sharing the tasks of both groups and developing priority schedules that took both traffic and vulnerable periods into account, the effective number of patrols could be increased without increasing budgets or manpower. However, to achieve this cooperation, both sides had to invest in the training and in each other’s patrol targets (How many traffic violations went undetected? How many houses were unobserved?). These compromises required negotiations between the two units, which had never collaborated in this way before. The resulting operating procedures took time and effort, demanding that the unit heads and their senior teams build a constructive relationship. It took over a year to achieve, but the end result was effective because they had come to have a shared vision and the confidence to communicate effectively with each other and with their superiors.

What mattered during this process was not the derivation of an optimal set of KPIs, but the in-crease in communication and guid-ance which taught the two branch-es to collaborate. Only through this communication and learning were they able to change their behavior so that the strategy could be car-ried out. KPIs alone would have led to more isolated behavior, fol-lowing the letter but not the spirit of their goals and failing to under-stand the effects of their behavior on colleagues.

3. Comparison with Other Cascading Tools

There are certainly other cascading tools already in wide use. Four of the best known are: the balanced score card (BSC) proposed by Kaplan and Norton in 1983,5 the Hoshin Kanri Planning process that Toyota and a few other Japanese companies began to develop in 1950,6 the Objectives and Key Results (OKR) application invented by Andy Grove at Intel in the 1980s,7 and the strategy briefing process proposed by Bun-gay (2 011).8 The strengths and weaknesses of these methods are laid out in Table 1.

| Balanced Score Card (BSC)(Kaplan and Norton 1983) | Hoshin Kanri(Toyota 1950) | Objectives and Key Results (OKR) (Grove 1985) | Strategy Briefing Process (Bungay 2011) | Cascading Trees | |

| Logic | 1. Develop strategy; 2. Map; and 3. cascade using BSC performance dimensions: financial, customer-facing, process, and learning/change; then 4. Implement operational execution; and 5–6. monitor and learn as the strategy unfolds and is adapted to the environment. | Establish an organizational vision and mission, with strategic (market-oriented) objectives, and cascade them with the Hoshin Planning (“X”) matrix, then execute with Kaizen and TQM tools. | Articulate ambitious goals (tangible, objective, high-value creating) and required measurable results to work toward (not actions). | Senior managers answer the question, “What do you want me to do?” Articulate strategic intent, how the pieces fit together, and their priorities, and connect them to high-level tasks. | Give high-level mission/action targets and break them into lower-level contributing actions and targets. Repeat going down 2–3 levels and negotiate the appropriate interdependent actions at each level. |

| Strengths | Cohesive institutional approach – this is the most widely used strategy mapping tool. | • Proven at operational level since the 1950s. • Emphasis on bottom-up and cross-functional management. • Integration of unit-level goals with daily tactical management. | Strategic initiatives oriented around results, and transparency in the organization by sharing OKRs between units. | Questioning and communicating the strategy. | • Transparency and clarity. • Identify and negotiate areas of interdependency. • Empower creative actions at each level. • Bottom-up input of both constraints and opportunities. |

| Limitations | • The BSC dimensions risk being used generically as pre-defined quality dimensions that hinder a truly differentiated personalized strategy. • The execution premium process has a strong top-down emphasis; the feed-back cycle emphasizes the success of the strategy and underplays input from lower levels and negotiations between units, potentially hindering organizational creativity and enthusiasm. | • There is a risk that the strategic market-oriented objectives and the operational (Kaizen) actions will be only weakly connected – the Hoshin Planning matrix quickly becomes too complex for causal transparency and flexibility. • Can become heavily bureaucratic. | • No actions included; therefore the tool stays at strategic level, not linking strategy to daily operations. • Negotiations of inter- dependencies and thus collaborative problem-solving are not included, leaving the focus on solitary efforts. | Similar to the first step of the cascading tree, but does not address the middle and front-line levels. This tool is largely useful at the senior management level. | Can become complicated if not based in a disciplined process of collaborative construction at each level and strict prioritization. |

A cascading tree offers an intelligent compromise – an explicit guide to constructive top-down, bottom-up, and cross-unit negotiation processes that build common understanding and alliance – emphasizing a collaborative process.

All tools have limitations. The BSC has often been used as a generic indicator (rather than articulating unique qualities) and has a top-down flavor that does not bring out the best in employees. Hoshin Kanri is perhaps the closest method to what we propose, but it is most effective within operations (already two levels down in our cascading tree). When an organization starts the process with a high-level strategy, the Hoshin matrix becomes extremely complex and process-heavy. OKR focuses on individual goals for change, yet, while acknowledging the benefits of transparency, it does not address interdependency or collaborative problem-solving. The strategy briefing process focuses on articulating strategic trade-offs and priorities at the top level, and on the goals and actions of senior executives, without connecting to the front line. Our cascading tree offers an intelligent compromise – an explicit guide to constructive top-down, bot-tom-up, and cross-unit negotiation processes that build common under-standing and alliance – emphasizing a collaborative process. Managers have to work for it, but it enables true strategic customization, with-out becoming a heavy-handed bureaucratic process.

4. Case Example: Sinyi Realtors

There is ever increasing pressure on companies to serve multidimensional constituencies and goals, for their private shareholders, financial markets, regulators, customers, and society. The traditional simplicity of maximizing shareholder value has come under attack, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, as being insufficient. Moreover, in an age in which society increasingly expects companies to consider the environment, employee benefits, and socie-tal contributions, firms must devise multifaceted strategies that embrace the deep conflicts between multiple goals. How can these complex demands be translated into operation-al targets?

Let us look at one company that has made ethical business its core principle, the Taiwanese real estate broker Sinyi Co. Sinyi was founded in 1981 in Taipei by Chun-Chi Chou and has, since the turn of the century, be-come the largest and most respect-ed real estate brokerage in Taiwan. It has a 15 percent market share, revenues of US$190m, profits of US$27m, and, as of 2016, 3,000 employees. Initially, Mr Chou found real estate to be a scattered industry in which the practice referred to as “earning the price spread” was common – if the final purchase price was higher than the seller’s original minimum price, the agency would appropriate the difference along with the (legal) commission. One of the first principles that Mr Chou introduced was that his firm would not use this unethical method. Instead, Sinyi would offer the customer total transparency. The company expanded this first practice over time into a range of service innovations, all aimed at serving the customer in an ethically clean and transparent way. This philosophy was eventually formalized in the company’s mission:

Our purpose is to foster secure, speedy, and reasonable realty transactions through the synergy of expertise and teamwork, providing Sinyi’s employees with a secure working environment in which to grow while generating reasonable profits to sustain the group’s survival and development.

This mission statement sets sever-al goals, balancing the benefits to Sinyi’s stakeholders: customers, employees, shareholders, society, and the environment. Sinyi is a for-profit organization, but it does not pursue profits to the exclusion of every-thing else. Having begun with the principled decision to forgo price-spread arbitrage it went on, without direct compensation, to introduce additional customer benefits over the years, such as offering customers full coverage for any disagree-able surprises in their new property. Sinyi also leads the way in reporting its environmental footprint and contributes generously to civic projects in its communities.

Top-Down Cascading

Strategy cascading in a company such as Sinyi has a business component but is also rooted in collaboration and common beliefs, without which the multiple stakeholder core of its ethical principles would not operate in a balanced way. As a result, (even our simplified representation of) Sinyi’s cascade strategy requires at least two cascading trees. The first concerns revenue, garnered through a differentiated strategy of providing customer service and earning customer trust. This position cascades into operational targets and process-es in a standard quantified way, as shown for two levels in Exhibit 4.

While the exhibit shows the tree for the sales target (revenues and market share), the numerical values are omitted for reasons of confidentiality. The higher level reflects strategic priorities: employees must buy into and live the premise that customer trust and ethical behavior translate into business. Sinyi doesn’t just sell houses; it sells service. Providing high quality service is therefore a high-level action and its processes, such as consistency and speed, must support sales. Each high-level action has a target: all employees must fulfill the trust value; quality of service is formally tested by various measures of customer satisfaction administered not by anyone in sales, but by a separate quality department; and customer interactions and conversions per branch and per month are subject to an assortment of efficiency measures.

Exhibit 4: Cascading of sales targets at Sinyi

The second level actions sup-port the first level targets, embodying the overall strategy. The left column shows that Sinyi prioritizes employee training, both formally and through cultural immersion. The center column supports client satisfaction, emphasizing the helpful and problem-solving nature of the individual realtor ’s work. Transparency, including openness about price range or other bidders, is built into the process. This column also de-scribes additional services such as guarantees and case-by-case add-ons reflecting the needs or desires of individual customers. The right column supports this work by laying out standard operating procedures (SOPs) which structure the sales-person’s work as well as the accompanying legal functions, and which ensure that the team collaborates and shares information. (The legal department has a separate set of process goals which have allowed it to reduce turnaround time by a third over the last five years.)

These formal business goals do not fully capture the ethical principle of sharing benefits with stake-holders. The sales goals are founded on the assumption that being ethical builds trust and good business, but stakeholder ethics also comprise a goal in their own right. So they also need to be connected to operational activities throughout the company. The second cascading tree, in Exhibit 5, delineates these connections.

The firm’s target is to continue to clearly differentiate itself as the most ethical player in the industry. This target is not aligned with the sales target but intersects with it. Combining both in one tree would result in confusion rather than transparency, so the company instead created two trees (pretty much the upper limit of complexity that a cascading tree will support). The ethics target is supported by four high-level goals: investments that explicitly acknowledge the needs of all stakeholders; ethical employee behavior (in accordance with company norms); a chief ethics officer, installed in 2010, who embodies employee centeredness and ethics; and the establishment of specific incentives. Each goal has a target, from “make all projects follow our principles” to “incentivize ethical behavior throughout.”

Exhibit 5: Cascading of ethics across the company

As in Exhibit 4, we see a strong emphasis on HR practices, not only on training but also on the selection of new employees according to their interest in others and their ability to be considerate and collaborative.

The chief ethics officer (third action) acts both as the conscience of the organization, informally encouraging employees to abide by its ethical principles, and as a catalyst for innovation. These roles necessitate a close relationship between the CEO and the chief ethics officer. For ex-ample, the chief ethics officer gives a short presentation at every meeting of the TEM, reminding attendees that the ethical principles of the business are a priority. The chief ethics officer also resolves dilemmas and conflicts within the organization. When two salespeople disagreed about sharing the commission for a large sale they had both worked on, the chief ethics officer reminded them of the Sinyi principle that taking advantage of others is a sin. He advised the more senior salesperson to concede the larger share of the commission to the more junior because senior staff have a responsibility to help and educate junior staff.

Sinyi has a similar policy for incentive structures, making commissions smaller relative to salaries. A Sinyi commission is about 12 percent of the company’s fee (compared to 20-30 percent elsewhere), of which one-third goes to the team. This practice encourages teamwork and ethical, customer-oriented service to a greater degree than those of competitors. Violations of the company’s customer service policies, for person-al profit or any other reason, result in immediate punishments including public shaming and fines (though the shaming is considered more severe). Meanwhile, teamwork and voluntary engagement in community activities are encouraged and informally rewarded.

We succeed not in isolation, but through collaboration amid interdependency.

Horizontal Communication

Sinyi’s practices ensure that all its employees understand and represent the company’s values. In our interviews at Sinyi, we found that workers at all levels demonstrated a clear under-standing of what makes Sinyi unique. As their chief ethics officer puts it, “people must believe that this positioning can breed success.” Sinyi’s employees also expressed confidence that, when necessary, their ideas will be heard by top management. The cascading processes at Sinyi are not cold and mechanical; they embody the values of the own-er, the CEO, and the senior team. As a result, some of the cascaded goals affect the entire organization, revealing its broader interdependence. The initial six-month training, for example, certainly covers effective selling (“It taught me how to speak to people,” said one salesperson), but it also encompasses collaboration, empathy, and taking care of each other as ends unto themselves, not just as business goals. By encouraging sales-people to engage in their communities, the company finds business opportunities and also adds value to those communities without directly measuring the value of community contacts converted in to customers. These actions, laid out across sever-al cascading trees, acknowledge that we do not succeed in isolation, but through interdependency.

And Sinyi has a range of goals which would never work without interdependency or without each member of the organization sharing a common understanding of the company’s mission and values. Various HR practices guide the selection and training of employees so that they learn, in their first year with the company, the importance of this balance and how to achieve it. In the words of Sinyi’s chief ethics officer, “We tell our people that quality, transparency, and honesty toward the customer will lead to profitability. The salespeople must believe this; otherwise our company does not work. If we execute the business successfully in this way, we are generating a profit machine, with the employees at the center, with which we can then also in-crease the benefits to the environment and society.”

Bottom-Up Innovation

The goals we have discussed come largely from a vision of the business which comes down from the top. For twenty years Sinyi’s competitors have striven to usurp its position by adopting similar language and promising customers the same integrity. Although none have yet matched Sinyi’s consistency in customer service, the company has to evolve constantly to stay ahead. Sinyi has therefore consistently innovated new services over the last twenty years.

Such guided innovation is ideal for nurturing projects that address weaknesses (e.g., process improvements in response to customer feed-back) and for taking advantage of strategic opportunities (such as a new management information system that improves workers’ knowledge of their customers, sales re-cords, and process integration). The TEM agrees upon these projects be-fore handing them over to the strategy office and the customer service department.

However, employees at all levels are encouraged to initiate activities and influence goals, driving innovation and change from the bottom as well as from the boardroom. Sales-people have a budget with which to test new customer service ideas. One salesperson, learning that her client did not like to reuse slippers others had already used, bought some disposable slippers before a house visit. Her experiment was so successful that it was formalized as a standard option.

Front-line employees are encouraged to send messages with ideas for change to both the CEO and the chief ethics officer. These officers read and responded to each mes-sage, and a few result in commendations or follow-up projects. Store and regional managers are asked to bring innovation ideas to the TEM for discussion. And Sinyi continues to steadily improve its operating performance, introducing roughly one major new service per year, including a takeback guarantee covering problems that are discovered after purchase, and an investigative service to determine whether any-one has ever died in the house (an important issue in Chinese culture).

Front-line salespeople who can change their processes feel a sense of ownership – they know they have a voice and influence which causes them to identify with the organization and willingly go the extra mile.

Salespeople can also initiate formal changes to the company’s process. For example, the current stock of houses for sale used to be visited weekly, every Friday. But the sales staff found that this schedule was sometimes too slow to allow them to effectively compete for desirable properties, so salespeople are now allowed to visit a new house any time, once it has come up for sale. They discuss ideas like this in the daily morning meeting, a practice very much in the spirit of continuous improvement in total quality management. Because of their direct input, the salespeople feel that, although it is formally owned by the customer service department, they also own the SOP, and that it reflects their knowledge and shared best practices. Of course, not all proposals are accepted: one salesperson experimented with thoroughly cleaning a house for the buyer in hopes of triggering a decision, but the company rejected making cleaning part of the SOP because it would have been economically burdensome. Nonetheless, front-line salespeople who can change their processes feel a sense of ownership – they know they have a voice and influence which causes them to identify with the organization and willingly go the extra mile.

In flexible and innovative companies, strategic goals change and evolve with the information that arises though the bottom-up initiatives.

5. Strategy Execution as a Process

Finally, the proposed cascading system can help organizations to adapt. Management scholars agree that there is a need for adaptable strategies which respond to the fun-damental uncertainty of the world around us. The time has passed when strategy was a static set of de-tailed goals, planned and optimized. Yet managers still know too little about how to set up and support adjustments of strategy in response to changes in the environment. One clearly demonstrated path to successful adaptation is the process we have described in this article.

Exhibit 6: Strategy cascading as a creative process

Exhibit 6 illustrates that adaptive strategy execution is a cauldron of ideas and decisions which circulate in all directions. At the top, there are broad goals responding, with the help of formal analysis and decision tools, to the societal, technological, and market environment. These goals need to be translated into high-level operational targets (in this case “improvement and productivity” and “new products and innovation”). The top-down arrow, then, corresponds to our high-level cascaded goals. We have found that top management teams have the capacity to pursue and supervise perhaps fifteen to twenty strategic change projects on top of their usual responsibilities.9 Most of these changes are compatible and can be pursued within the existing structures and processes. For these, cascading asks each unit, “What can you do to make this happen?” Few strategic projects cannot be accomplished within the existing structures. These few may require an additional unit with different experts, equipment, or perhaps entrepreneurial approaches. And for these, the cascading needs to start from scratch, just as it would for any major project which assigns people to new tasks not already being performed by incumbents.

In all the strategic changes which are compatible with existing structures, information also flows up from the bottom, carrying not only many small improvements but also higher-impact ideas. These are collected through various mechanisms and drive the generation of innovative initiatives in the middle. For example, the company where we first saw the cascading tree in action changed its operations strategy from “cost leadership” to “time leadership” when front-line personnel suggested that, by speeding up processes, customer service could be transformed into a competitive weapon and, because speeding up would require operations to be eliminated, costs would also decrease. There are some well-known examples of similar strategy changes. In the 1980s Intel was transformed from a memory chip manufacturer into the market lead-er in processor chips after a bot-tom-up revolution in which middle management eventually persuaded their seniors. Likewise, in the 1990s, the ideas of middle management, which the upper levels took a decade to accept, reorganized IBM into a service business, converting hardware production units into internal suppliers. Bottom-up ideas don’t just drive improvements on existing goals, they also introduce new performance elements (new services, new customers, new ways of defining value) that surpass existing strategic goals and help the company to innovate.

All of the arrows (which rep-resent information and communication flows) should be support-ed by institutional mechanisms and processes, as well as cultural norms that encourage employees to contribute. Alignment, compatibility, and mutual creativity should be expected to be negotiated be-tween units, divisions, and teams, again supported by a combination of mechanisms including process-es and cultural routines and habits. These institutional processes are not necessarily to be found in process handbooks, but are both formal or informal actions that are widely accepted and recurring. Formal actions might include sanctioned and resourced six-sigma (continuous improvement) projects, benchmarked across several units, while informal actions could be talking to external contacts or discussing best ideas and the interactions between them with col-leagues.

This system of top-down, bot-tom-up, and horizontal cascading orients employees toward shared goals and emerging changes in the environment, as well as promoting horizontal transparency and alignment. We call this situation a cauldron because, to an outsider it may look like a chaotic stew of seemingly unconnected activities. But the outsider does not see the combination of processes and cultural rules that aligns the system with shared goals. The cauldron does require patience and persistence, but as one Sinyi senior manager put it: “Gaining everyone’s trust is very difficult and a never-ending journey, and it is constantly subject to undermining and misuse, by customers and sometimes employees. Our results indicate that the public honors our efforts, and our reputation is unparalleled. This rep-resents no laurels on which we can rest, but an encouragement to keep moving forward.” And strategies rarely create a monopoly on which an organization can rest securely. Instead, strategy offers a foundation from which to keep trying. Even Sinyi’s service portfolio has changed dramatically over the last twenty years, yet the underlying values (of sharing with customers, employees, and society) remain.

No tool is universal, no matter how you stretch it. As an organization grows, even the cascading tree reaches its limit. Sinyi uses horizontal collaboration targets, rather than

In flexible and innovative companies, strategic goals change and evolve with the information that arises though the bottom-up initiatives.

KPIs, to strengthen employee alignment with its overarching goals. But as a company expands and the numbers in its hierarchy increase, people at the lower levels become irresistibly tempted to focus on their local KPIs and the grander purpose begins to recede. Another organization we worked with grew from approximately 10,000 people to nearly 20,000 (six times larger than Sinyi). This organization opted to reducespecifically local KPIs (however well designed) and to emphasize higher-level KPIs. The change helped people to recognize the bigger picture and understand that they were all in the same boat, encouraging dynamic negotiations about actions that might not improve an individual’s success but would help wider groups to achieve larger goals. To keep such a large organization on track, strategy alignment must be loosened, or the levels of detail in the cascading tree limited.

In flexible and innovative companies, strategic goals change and evolve with the information that arises though the bottom-up initiatives. There is no precise recipe for how strategy cascading and execution should look. Their organizational content depends on economics, markets, and culture along with myriad smaller factors. Nonetheless, despite the case-to-case details, certain core elements exist in any cascading system that strategically aligns and executes adaptation. Excellent cascading allows an organization to change its strategies without having to manage a crisis.

Christoph Loch is a Professor of Technology and Op-erations Management and Dean of the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School. For thirty years, he has worked with organizations of various types on executing innovation, managing complex and uncertain projects, and emotionally motivating professional employees.

Stylianos Kavadias is the Margret Thatcher Professor of Technology and Operations Management and Director of the Entrepreneurship Centre at the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School. He is an expert in product development and innovation, and on the entrepreneurial journey of new ventures

Yang Bai-Chuan (B.C.) is an Associate Professor of Business Administration and a member of the board of trustees at Fu Jen Catholic University in Taipei. He serves as Chief Ethics Officer and adjunct Chief HR Officer at Sinyi Realty Group. He is dedicated to advancing the application of ethics theory in business practice.

Appendix: A Brief Overview of Academic Work on Strategy Cascading

For a long time, both academics and practitioner professionals have wrestled with the problem of strategic alignment of organizational actions. They have approached it in four ways, none of which ad-dressed it systematically. Resource allocation theorists approached strategy execution on the notion that action occurs wherever the money goes. Strategy execution can certainly be quite formal, some-times involving metrics, but it can also be driven by culture.10 Execution has likewise been approached as a decision between several possible resource allocations, using capital budgeting methods, or through the more qualitative lens of strategic program port-folios.11 But in order to allocate resources effectively, companies must combine considerations of strategic action portfolios, financial circumstances, and company culture.12

Agency theorists observed that the firm’s objective might not be that of the employee (agent), and suggested that compensation and incentives might be important to aligning strategies.13 A famous paper foreshadowed the dangers of untargeted incentives, demonstrating the fallacy of “rewarding A while hoping for B.”14

Other scholars approached strategic alignment as a problem of communication and coordination. They argued that, while rewards and metrics cannot be viewed independently from strategy and structure,15 the firm must decide what to communicate to its employees as strategy, and then use what has been communicated to drive reward systems.16 The clarity with which a strategy is explained to organizational units is thus a key enabler.17 Moreover, both vertical alignment and horizontal communication and collaboration are then required to achieve alignment.18 This view is consistent with our cascading tree proposal.

Finally, analytical hierarchical planning (AHP) strove to formalize the link between strategic goals and the complex execution decisions required at different levels of the hierarchy.19 While offering interesting insights into the methodology of deconstructing complex decisions into smaller and simpler choices, AHP has been criticized for its restrictive formalism and for trying to automate a process that relies upon subjective evaluations and perspectives.20

Table 1 examined four important cascading tools that are currently in wide use. Other scholars have emphasized the importance of alignment, the need for employees to understand, and identify with, the over-arching goals, so that their actions will strengthen the company’s strategic position.21 Managerial recommendations tend to echo the concerns raised in the theoretical literature that aligned measures must be subject to modification from the bottomup in response to changes and new ideas.22 Our cascading tree proposal fulfills these needs. There is also a longstanding discussion of the measures that influence behavior. For example, FAST (frequently discussed, ambitious, specific, and transparent) measures have supplanted the previously popular SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound) model.23 While this discussion is certainly important, it does not directly address the problem of alignment. Indeed, as we have described, some companies have chosen to reduce the specificity and direct consequences of performance measures in order to achieve collaboration throughout the company and support the (fuzzier) whole.

Endnotes

- We observed this for the first time many years ago when it was used by a successful leader, Dr. Jessen, at Festo.

- Cross-functional collaboration is illustrated in a case study of changing manufacturing lines to maintain the productivity of aging employees, in Loch, C. H., Sting, F. J., Bauer, N. N., Mauermann, H. H. 2010. How BMW is defusing the demographic time bomb. Harvard Business Review, 88(3), 99–102. The wider need for horizontal collaboration is documented in Sting, F. J., Loch, C. H. 2016. Implementing Operations Strategy: How Vertical and Horizontal Coordination Interact. Production and Operations Management25(7), 1177–1193.

- This has been shown in Kim, Y. H., Sting, F. J., Loch, C. H. 2014. Top-down, bottom-up, or both? Toward an integrative perspective on operations strategy formation. Journal of Operations Management, 32(7–8), 462–474.

- Sting, F. J., Fuchs C., Schlickel M., Alexy O. 2019. How to Overcome the Bias We Have Toward Our Own Ideas. Harvard Business Review, Online.

- Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. 1992. The Balanced Scorecard: Measures that Drive Performance. Harvard Business Review (January–February), 71–79; Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. 2000. Having Trouble with your Strategy? Then Map It. Harvard Business Review, September–October, 167–176. The most advanced discussion of their strategy cascading process is in Kaplan, R. S., Nor-ton, D. P. 2008. Execution Premium: Linking Strategy to Operations for Competitive Ad-vantage. Boston: HBS Press.

- Tennant, C., Roberts, P. 2001. Hoshin Kanri: a tool for strategic policy deployment. Knowledge and Process Management 8(4), 262–269. See also Waldo, W. 2019. The seven steps of Hoshin Kanri Planning. Lean Methods Group, https://www.leanmethods.com/resources/articles/seven-steps-hoshin-planning/

- Grove, A. S. 1985. High Output Management. London: Vintage. Later discussions can be found in Zhou, H., He, Y. 2018. Comparative study of OKR and KPI. International Conference on E-Commerce and Contemporary Economic Development, ISBN 978-1-60595-552-0; and Google’s OKR Playbook at https://www.whatmatters.com/resources/googles-okr-playbook.

- Bungay, S. 2011. How to make the most of your company’s strategy. Harvard Business Review 89, January–February, 132–140.

- See Sting et al. 2016, from Endnote ii.

- Bower, J. L. 1970. Managing the Resource Allocation Process, Boston: HBS Press. See also Burgelman, R. A. 1983. A Process Model of Internal Corporate Venturing in the Diversified Major Firm. Administrative Science Quarterly 28, 223–244.

- Harris, M., Kriebel, C. H., Raviv, A. 1982. Asymmetric Information, Incentives and Intrafirm Resource Allocation. Management Science28(6), 604–620. See also Cooper, R. G., Edg-ett, S. J., Kleinschmidt, E. 2001. Portfolio Man-agement for New Products. Perseus.

- Loch, C. H., Kavadias, S. 2011. Implementing Strategy Through Projects. Chapter 8. In: Morris, P., Pinto, J., Söderlund, J. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook on the Management of Projects. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 224–251.

- Very influential early work in this stream were Grossman, S., Hart, O. 1983. An Analysis of the Principal-Agent Problem. Econo-metrica 51(1), 7–45; and Holmström, B. 1979. Moral Hazard and Observability. Bell Journal of Economics 10(1), 74–91.

- Kerr, S. 1975. On the Folly of Rewarding A, While Hoping for B. The Academy of Management Journal 18(4), 769–783.

- Galbraith, J. R. 1974. Organization Design: An Information Processing View. Interfaces4(3), 28–36.

- Rotemberg, J., Saloner, G. 1994. Benefits of Narrow Business Strategies. American Economic Review 84(5), 1330–49.

- Hutchison-Krupat, J. 2018. Communication, incentives, and the execution of a strategic initiative, Management Science 64(7), 3380–3399; and Hutchison-Krupat, J., Kavadias, S. 2015. Strategic resource allocation processes: top-down, bottom-up, and the value of strategic buckets. Management Science 61(2), 391–412.

- See Sting et al. 2016, from Endnote ii.

- Saaty, T. L. 1980. The Analytic Hierarchy Process, New York: McGraw Hill; Wind, Y. Saaty, T. L. 1980. Marketing Applications of the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Management Science 26, 641–658.

- Dyer, J. S. 1990. Remarks on the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Management Science36(3), 249–258.

- Examples are shown in: Kim, W. C., Mauborgne, R. 2015. Closing the Gap Between Blue Ocean Strategy and Execution, HBR.org 05. February 2015, adapted from: Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant, HBS Press 2015; Loch, C. H., Tapper, S. 2002. Implementing a Strategy-Driven Performance Measurement System for an Applied Research Group. Journal of Product Innovation Management19, 185–198; and Rucci, A. J., Kirn, S. P., Quinn. R. T. 1998. The Employee-Customer-Profit Chain at Sears. Harvard Business Review76(1) (Jan–Feb), 83–97.

- Sull, D., Homkes, R. Sull, C. 2015. Why Strategy Execution Unravels—and What to Do About It. Harvard Business Review, March, 2–10.

- Sull, D., Sull, C. 2018. With Goals, FAST Beats SMART. MIT Sloan Management Review.