Dave Ulrich

Rensis Likert Professor, Ross School of Business, University of Michigan Partner, The RBL Group

Philosophers for generations have explored how to make knowledge productive. Each of us must find a personal pathway between research and practice. Drawing on his personal experience in both academics and consulting, Dave Ulrich shares an approach to blending the fields of research and practice, giving us hands-on ideas for making our knowledge productive.

Everyone engaged in management (academics who do research, practitioners who govern, consultants who advise) navigates the polarity of theory versus practice. This essay suggests ways to understand, navigate, and find a personal pathway through trade-offs between theory/research versus practice/solution.

Philosophers for generations (e.g., Aristotle, Plato) and, more recently, epistemologists (John Locke, David Hume, Rene Descartes) have explored the nature of knowledge including the dialectic of inquiry (theory) versus action (practice), or how to make knowledge productive. Legacy thinkers have suggested that bridging theory and practice benefits both:

- He who loves practice without theory is like the sailor who boards ship without a rudder and compass and never knows where he may cast. – Leonardo da Vinci

- Experience without theory is blind, but theory without experience is mere intellectual play. – Immanuel Kant

- In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice, they are not. – Albert Einstein

- There is nothing so practical as a good theory. – Kurt Lewin

These theory/practice debates regularly occur in biology, education, engineering, law, medicine, psychology, sociology, and management.1 On the one hand, academics, as organization and management scholars, often focus on developing theories to explain timeless patterns of managerial activity validated by research using the scientific method of hypothesis testing and incremental knowledge accumulation. Success comes with publication in leading academic journals, and the process is institutionalized through promotions (tenure). On the other hand, practitioners (managers or consultants), face pressing problems that require timely solutions. Success is measured less by the theoretical richness of ideas or research rigor and more by actions that resolve a pressing challenge so that stakeholders get results.

Colleagues have analyzed and lamented the increasing gap between academic rigor and managerial relevance because of differing goals, unique language, incentives, time frames, and skills.2 Many have explored closing this gap with initiatives such as action research, action learning, appreciative inquiry, design thinking, evidence-based management, reflective practice, and other approaches.3

Ultimately, each individual discovers a personal pathway through this theory/practice thicket. Learning from others’ explorations highlights options to make knowledge productive. This essay proposes a personal coaching guide by reviewing three choices in

my journey that might be relevant for you: [1] challenge traditional assumptions about knowledge, [2] claim your personal choice, and [3] if inclined, engage in relevant research or pragmatic theory to meld theory/research and practice/solution.

[1] Challenge Traditional Assumptions about Knowledge

At his retirement celebration, one of my mentors reviewed the message he was taught decades ago in a top graduate school about the hierarchy of scientific scholars: mathematicians were at the top of the pecking order, followed by physicists, natural scientists (biologists, chemists, earth scientists), economists, social scientists (sociology, psychology, political scientists), with management scholars (often in business schools) at the bottom of this ranking system.

In a similar way, some believe in a hierarchy of knowledge providers, with those who explore theory/ research and publish in x, y, and z journals followed by those who teach next-generation students, followed by consultants who offer advice, and ultimately managers who act. Such comparative assumptions exacerbate the theory/ research versus practice/solution gap leaving each group justified in stereotyping and denigrating the other. Academics might label practitioners as quick-fix charlatans, purveyors of silver bullets, or faddish. Practitioners might label academics as ivory towers, egg heads, quixotic, and irrelevant.

A more positive and bridgebuilding assumption is that thoughtful individuals make conscious choices about where they want to primarily contribute their intellectual energy and how they define success. For academics, rigor is relevance; for practitioners, relevance improves with rigor. As such, ranking a hierarchy of professional identity is less relevant than rating the quality of work within that identity. Ranking one professional orientation above another is demeaning and dysfunctional.

If you cling to the assumption prescribed to my mentor (which he did not believe or practice) about a hierarchy of knowledge, then you will never bridge the gap between theory/research and practice/solution. A virtuous spiral starts with mutual respect where each side appreciates the other. With respect for others, you can better accept your personal choices.

[2] Claim Your Personal Choice: What Do I Want?

With mutual respect for your and others’ career choices, you then face the never-ending personal challenge of knowing what you want. Abraham Maslow wisely said, “It isn’t normal to know what we want. It is a rare and difficult psychological achievement.” Without knowing want you want, others may define your wants for you, often not in your long-term interest. Yet, this seemingly simple question becomes complex because answering it requires an awareness of personal strengths, passions, and values. The self-reflection questions to probe what you want most are not new but worthy of continued musing:

- What is the identity I would like to be known for?

- What problems do I want to solve?

- Who is the audience I would like to spend time with and influence?

- What would be the indicators of my feeling successful?

- Who are the colleagues I most admire?

Answering these questions often comes from experience even more than intent:

- Am I more excited by an academic publication or helping a leadership team solve a business problem?

- If I had to choose between presenting a paper at an academic conference or meeting with a senior business team, which would I chose?

- When I introduce myself to new groups, what is the first line of my identity?

- In my private personal musings, what do I most of ten think about – clarification of the new ideas or application of the ideas?

Almost everyone has personal experiences that help answer these self-reflection questions.

Early in my career, I was doing an all-day Friday leadership workshop for a senior business team. At the 9:00 am break, participants discovered that an activist investor had just gone from 4.9 percent to 15 percent stock ownership to greenmail the company. When executives returned from the break, they asked me about how to respond. I did not know what to suggest, so they dismissed me and engaged in a real-time problem-solving session. I went home and spent time seeking academic literature on how to battle greenmail, but, at that time, found almost nothing. So I spent time crafting a response and met again with the team on Tuesday. Together, we discovered an approach that helped the leaders through this crisis. This experience captivated me as I found helping them solve their real-time challenge was intellectually stimulating and emotionally meaningful.

Similar encounters with demanding challenges have occurred over and over again throughout my career as I have found that I seek and like to muse on complex, realtime, and undefined problems with unsolved questions:

- Why do firms in the same industry with the same earnings have different market value? This has led to years of studying intangibles and the leadership capital index.

- What makes an effective organization? This work pivoted a focus on organization as morphology and structure towards seeing organizations as bundles of capabilities.

- How does an organization create and implement a culture that delivers value to customers? This has led to the understanding of leadership and culture as brand from the outside in.

- Why do change initiatives not create sustained change? This has led to the work on leadership sustainability, change disciplines, and culture change.

- Even with all the research and efforts on employee sentiment (engagement, commitment, experience, well-being), why are employees not increasing their sentiment scores? In the book The Why of Work, this led to a synthesis of how to capture employees’ hearts as well as hands, feet, and heads.

- How do organizations wisely target their human capital investments when they often spend 1 to 3 percent of their annual revenue on talent, leadership, organization, or HR initiatives?

Often, initial answers to these (and many other) questions require creation of new explanations and ideas, which, over time will be tested and honed. I found I like being in the early 10 to 20 percent of the S-curve of ideas with impact, which requires creativity and exploration more than rigor and testing. In doing so, I like to create new knowledge that leads to productivity.

So what questions fascinate you? Shape your identity? Trigger your best thinking? Define your success? What impact do you want to have? Who is your audience? How do you define success?

As you define what you want, recognize that success requires both competence and commitment. Competence means you have the skills to do the task; commitment means the task is something you feel passion about and are dedicated to doing. To become a legitimate scholar requires extensive training and the ability to grapple with theoretical ideas and test them with scientific rigor. Rigor is the relevance of the scholarship discipline. To become a successful practitioner requires extensive experience to recognize and solve problems that deliver individual, business strategy, customer, financial, and community results. Commitment means having the endurance to stick with a pathway even through difficulties.

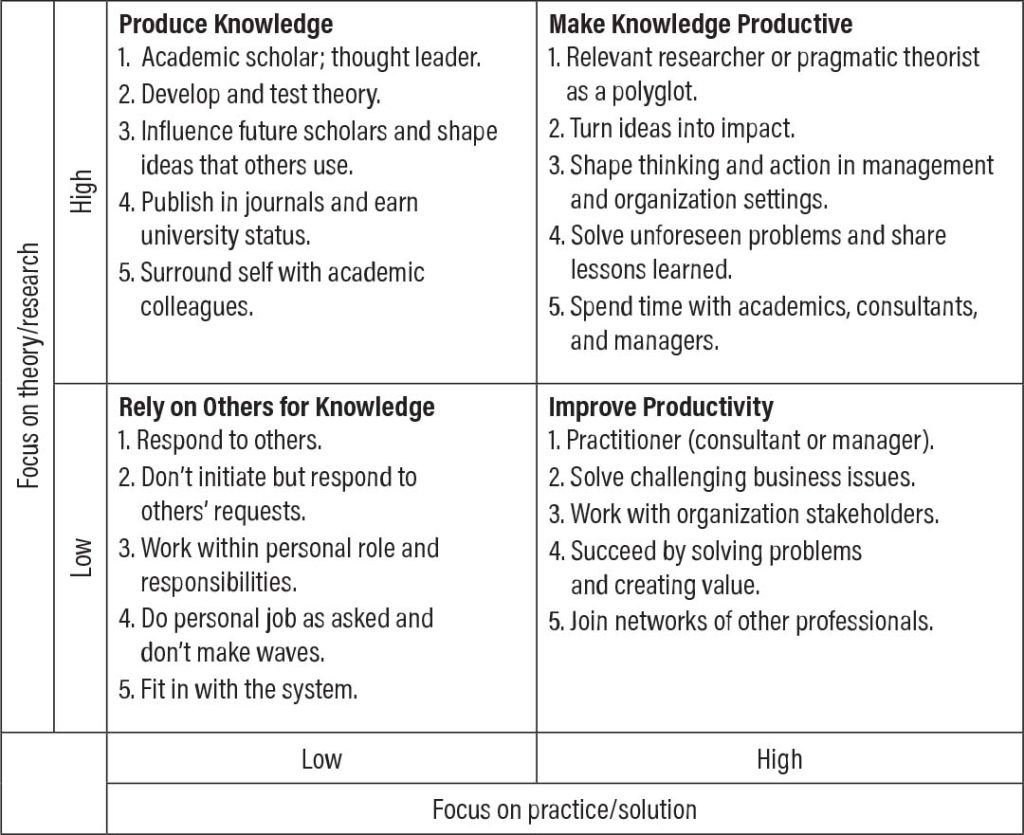

Knowing what you want also shapes short- and long-term actions. For example, publishing simply to get tenure and then moving to what you really want in terms of application is a misguided assumption and false positive. Doing so wastes many of your most productive years. This attitude implies a hierarchy (academic respect through tenure is more important than anything else). Focusing only on tenure ignores and belittles the price paid to do practitioner work. An academically elite colleague, soon after getting tenure, approached me and asked: “Now that I have tenure, I would like to consult. What should I do?” The implicit message was “How do I now go make more money by sharing ideas through consulting?” My colleague was surprised by my response: “Spend 80 to 100 nights on the road listening to, teaching, and coaching leaders so that you know what they are most interested in.” He was disenchanted with my response, believing that meeting tenure requirements implied a license to consult, when, in fact, he did not have much to say that was relevant to business leaders. The commitment to scholarship requires knowing theory and being able to do rigorous research to test it, which sometimes means rejecting ideas and revising and resubmitting until ideas are honed and accepted. The commitment to relevance means observing, hearing, and appreciating business challenges practitioners face, which sometimes means that anticipated solutions don’t work in changing business contexts. See figure 1 for a summary of these personal choice questions, which are very similar to the four quadrants based on the quest for fundamental understanding (theory/research) or consideration for use (practice/solution) and adapted to business school.4,5 Placing yourself in this grid is useful, both in the present and for your future.

Self-reflection questions:

- What is the identity I would like to be known for?

- What problems do I want to solve? Who is the audience I would like to spend time with and influence?

- What would be the indicators of my feeling successful?

- Who are the colleagues I most admire?

[3] Engage in Relevant Research or Pragmatic Theory to Mold Theory/ Research and Practice/Solution

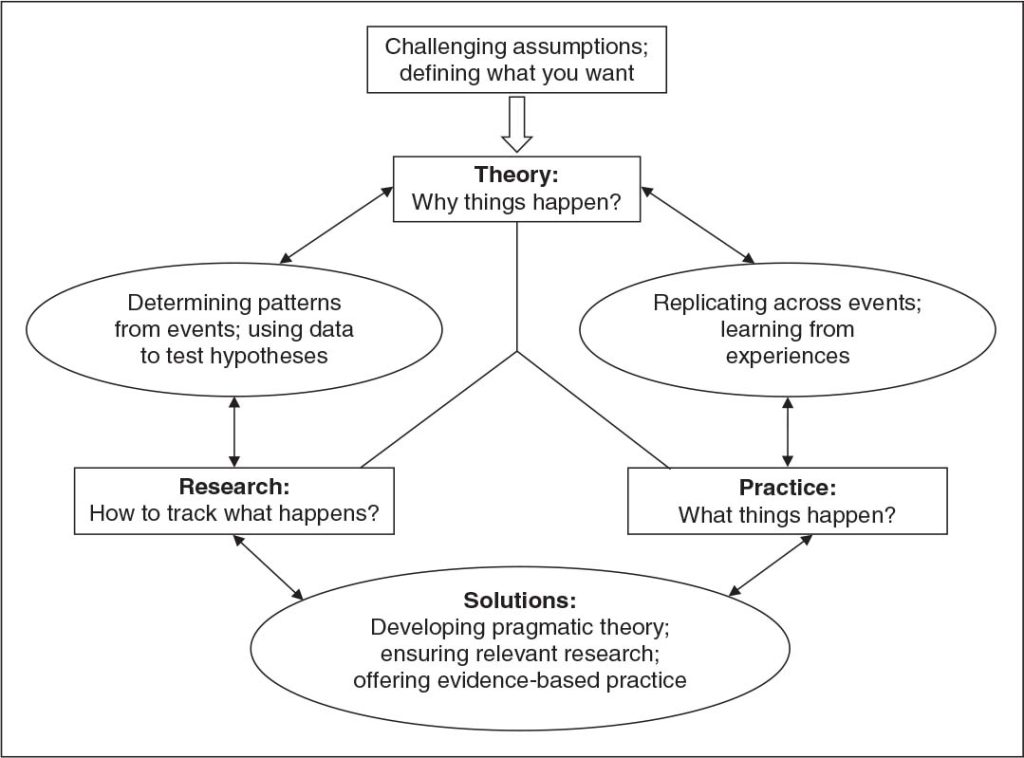

If you respect various identities and want to engage in the art of making knowledge productive (top right cell in figure 1) by melding theory and practice, let me offer a few suggestions. 6 As you respond to colleagues, you may be asked if you are more macro or micro? Focused more on theory, research, practice, or solutions? An academic or a consultant? Seeking fame or fortune? Your answer to most of these questions will be “yes.” You master making knowledge productive by becoming a polymath who is ambidextrous with a wide range of knowledge. To integrate theory, research, practice, and solutions, you need to connect and not separate ideas from action. Figure 2 lays out my logic for making knowledge productive through relevant research, pragmatic theory, and evidence-based practice leading to solutions.

- Theory answers the why question and helps frame problems so that findings can be replicated over time and settings.8 Theory without research is daydreaming; theory without practice is idle and esoteric thought. To offer sustainable explanations, theorists need to be committed to research that tests ideas and to practice that grounds ideas.9

- Research answers the how question and helps discover reality versus myth, to separate valid insights from popular opinion.10 Research without theory is unguided empiricism; research without practice is a convenience study without sustainability.11 Researchers need to know why they find what they find (theory) and how to make their findings useful to others (practice).12

- Practice answers the what question by experiencing and solving current business problems.13 Practices without theory are isolated and discrete events; practices without research are false hopes. Practitioners need to be rigorous in their thinking so that they are not carried away on the latest winds of popular management fads.

- Solutions result when theory, research, and practice come together to offer evidence-based insights that make knowledge productive.14

If you want to engage in the journey of making knowledge productive, let me suggest seven steps, consistent with other views, that have worked for me and might be adapted for you.

- Start by observing a phenomenon. Integration of theory, research, and practice requires grounding in a phenomenon. Phenomenologists encourage thinkers to experience, think about, and write about what is happening that is of interest to them. The phenomenon may come from observation of an individual, leadership, or organization challenge and often is something that is a bit quirky or unusual. I listed a number of these observations and questions above that have shaped my inquiry. One example that has captivated me is that firms in the same industry with the same earnings have different market values.

- Create your point of view. Once you have described a phenomenon, often with a question, probe why you think this might be happening. Your explanations draw on your experiences and knowledge and create your point of view. As noted above, figuring out why firms in the same industry with the same earnings have different market values led to our point of view on intangibles. Create your point of view before exploring other forces and innovative thinking deeper – you will then gain more clarity about the potential causes for the phenomenon.

- Discover other relevant perspectives. Once the phenomenon and explanations are proposed, systematically reviewing what others have said is helpful. Generally, many theoretical perspectives may inform and predict why things happen as they do with research that tests these theories.15 To unravel intangibles, we ended up reviewing economic, investor, and organization literatures. Because we had observed and described a clear phenomenon and explored why we thought it might exist, we were able to synthesize how others had tried to make sense of this market quirk that informed and validated our thinking. By drawing on the theoretical underpinning from others, we helped position our work in the knowledge network of what others have studied. Because we had thought a priori about our solutions, we were also able to discover how our ideas differed from current theory and research. From this work, we were able to identify specific questions we wanted to explore, which expanded the existing knowledge network. Without drawing on previous work, practitioners often repackage old ideas, not recognizing that others have often already made great progress on problems they are trying to solve. Sometimes, practitioners implement what others have done; at other times, when they recognize previous work, they are able to create new insights. Our work on intangibles lead to the leadership capital index and organization guidance system, novel ways to evaluate the market value of leadership and human capability that complements other work.

- Be rigorous in your methods. Research methods and statistical approaches allow you to answer your questions with discipline. The methods should match the research questions, ranging from exploratory and qualitative to analytical and quantitative. In our intangibles research, since many of the ideas were exploratory, we did extensive interviews to figure out how investors thought about human capability (talent, leadership, and organization). This led to other quantitative research that helped answer our questions about market valuation. Using current AI/machine learning technology, we were able to bring innovative data collection and analysis to the question of market value. As you make knowledge productive, you are likely to be asked, “How do you know your solution works?” Relevant research moves beyond personal opinions and isolated case studies to explore patterns and replication of ideas. Your research design and methods validate answers to the questions you want to answer.

- Tie findings back to the problem. Once you have done your research, you should close the loop and return to the original phenomenon. Have you added to the understanding of what is happening and why it is happening? Has your theory and research been able to offer new ways to think about and act on this phenomenon? In our intangibles work, we moved beyond some of the outstanding previous work on intangibles (patents, technology, brand) to explore a new category of intangibles (human capability). When you connect back to the phenomenon you are trying to solve, you are likely to build on existing work and create new insights, and your knowledge becomes productive.

- Learn. Learning is the ability to generate and generalize ideas with impact, so envisioning how your work will offer insights to multiple stakeholders is useful. What would those experiencing the phenomenon do differently? In our intangibles work on market value, what would we say to investors? Leaders? Scholars? Anticipating these conversations, what is missing in our work? In addition, what questions emerge or remain after answering the questions we started with? Learning means that with every set of answers come additional questions.

- Share insights. Ultimately, knowledge is productive when it is shared with others. This sharing may come in the form of speeches, blogs, reports, workshops, training, conversations, or articles. While many academic journals continue to be focused on the expansion of theory through the rigors of research, some publications attempt to bridge this gap. Management Business Review (MBR) has the goal “to bridge management practice, education, and research, and thereby enhance all three.” By modeling collaboration across eleven business schools, MBR also distributes ideas with impact by weaving together theory, research, practice, and solutions.

If you chose to make knowledge productive, these seven steps are not always linear or explicit, but they lay out the process for those who choose to participate in this work.

Conclusion: Turn My Experiences into Your Journey

The gap between theory/research and practice/solution can and should both continue and be bridged. Continuing the gap means that thoughtful colleagues have chosen where they want to engage. Some will choose to be academic scholars and others practitioners. With mutual respect, others will choose to be relevant researchers or pragmatic theorists to help make knowledge productive. The good news is that support for this bridging role is increasing with outstanding colleagues who share the agenda publication outlets to distribute ideas and institutional support with formal roles. The better news is that if you want to engage in making knowledge productive, you can do so to meet your personal career expectations.

Author Bio

Dave Ulrich is the Rensis Likert Professor at the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, and a partner at The RBL Group consulting firm. He is a celebrated author, has edited HR journals, has spoken to large audiences globally, has performed workshops for many Fortune 200 companies, and has coached successful business leaders. He is known for continually learning, turning complex ideas into simple solutions, and creating real value for those he works with. dou@umich.edu

Endnotes

- Please see:

Agrawal, V.K., P. Khanna, & K. Singhal. 2020. The role of research in business school and the synergy between its four subdomains. Academy of Management Review. 45, 896-912.

Churchman C. West and A.H. Schainblatt A. H. 1965. “The Researcher and the Manager:A Dialectic of Implementation,” Management Science. Vol. 11. No. 4, 69–87.

Duncan, Jack, W. 2017. Transferring management theory to practice. Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 17, No. 4. Published Online: November 30, 2017: https://doi.org/10.5465/255649

Gouldner, Ivin. 1956. “Explorations in Applied Social Science,” Social Problems, III pp. 169-81.

Pronko, N. H. (1982). Theory versus practice? Academic Psychology Bulletin, 4(3), 425–430. ↩︎ - Please see:

Stokes, Donald E. 1997. Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. K ieser, A., A. Nicolai, and D. Seidl. 2015. The Practical Relevance of Management Research: Turning the Debate on Relevance into a Rigorous Scientific Research Program. Academy of Management Annals. Pages 143-233.

Maertz, Carl P., Julie Irene Hancock, Paula Ann Kincaid, Cameron Noe; August 2023. What Has Empirical Turnover Research Offered Managers? Academy of Management Proceedings.

Shapiro, D. L., Kirkman, B. L., & Courtney, H. G. 2007. Perceived causes and solutions of the translation problem in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 249–266.

Shapiro, D.L., B.L. Kirkman. 2018. It’s time to make business school research more relevant. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr. org/2018/07/its-time-to-make-business-school-research-more-relevant ↩︎ - Please see:

Barley, S. R., Meyer, G. W., & Gash, D. C..1988. Cultures of culture: Academics, practitioners and the pragmatics of normative control. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 24–60.

Rynes, S. L. 2012. The research-practice gap in I/O psychology and related fields: Challenges and potential solutions. In S.W.J. Kozlowski (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 409–454). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ↩︎ - S tokes, Donald E. 1997. Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. ↩︎

- Agrawal, V.K., P. Khanna, & K. Singhal (2020): see note 1. ↩︎

- For a similar discussion, see Unruh, Gregory. The virtuous cycle of practitioner-based research: How academics repeatedly create groundbreaking management concepts. Working paper. ↩︎

- Please see:

Deadrick, D. L., & Gibson, P. A. (2007). An examination of the research–practice gap in HR: Comparing topics of interest to HR academics and HR professionals. Human Resource Management Review, 17, 131–139. Deadrick, D. L., & Gibson, P. A. (2009). Revisiting the research–practice gap in HR: A longitudinal analysis. Human Resource Management Review, 19, 144–153. ↩︎ - Please see :

K lein, H. J., & Potosky, D. 2019. Making a con-ceptual contribution at Human Resource Management Review. Human Resource Management Review, 29, 299–304.

Thompson, James D. 1967. Organizations in Action, New York. McGraw-Hill. ↩︎ - Bennis Warren G. 1965. “Theory and Practice in Applying Behavioral Science to Planned Organizational Change,” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 1, 337–359. ↩︎

- Rynes, S. L., Colbert, A. E., & Brown, K. G. 2002. HR Professionals’ beliefs about effective human resource practices: correspondence between research and practice. Human Resource Management, 41(2): 149–174. ↩︎

- Wright, P. M., Nyberg, A. J., & Ployhart, R. E. 2018. A Research Revolution in SHRM: New Challenges and New Research Directions. Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management, 36(3): 141–161. ↩︎

- Please see:

Lawler, E. E. 2007. Why HR practices are not evidence-based. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1033–1036.

Mohrman, S. A., & Lawler, E. E. (Eds.).(2011). Useful Research: Advancing Theory and Practice. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. ↩︎ - Rynes, S. L., & Bartunek, J. M. 2017. Evidence-Based Management: Foundations, Development, Controversies and Future. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 235–261. ↩︎

- Please see:

Grossman, Robert J. 2009. Close the gap between research and practice. HR Magazine, 54, 31– 37.

Kryscynski, D., & Ulrich, D. 2015. Making Strategic Human Capital Relevant: A Time-Sensitive Opportunity. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(3): 357–369. ↩︎ - Aram, J. D., & Salipante, P. F. 2003. Bridging scholarship in management: Epistemological reflections. British Journal of Management, 14, 189–205. ↩︎